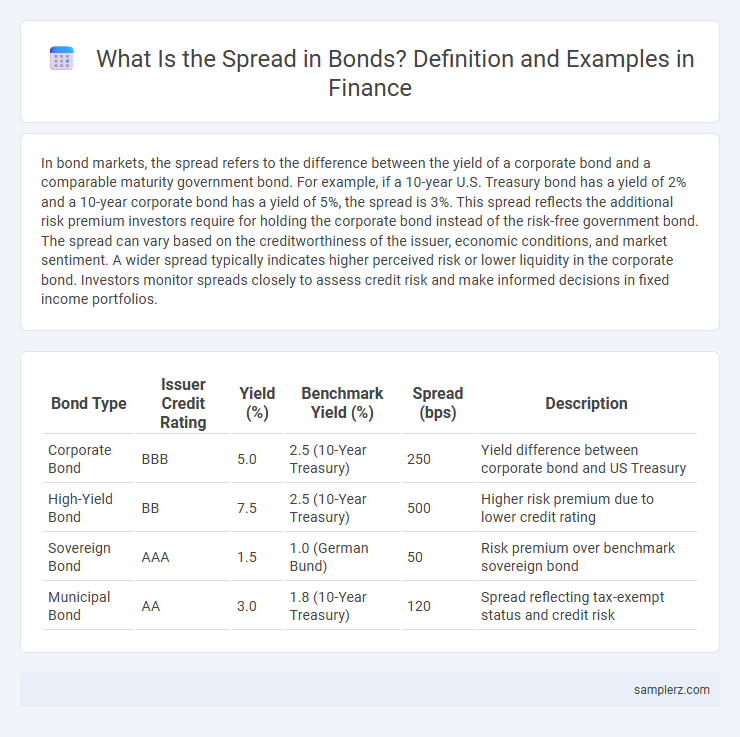

In bond markets, the spread refers to the difference between the yield of a corporate bond and a comparable maturity government bond. For example, if a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond has a yield of 2% and a 10-year corporate bond has a yield of 5%, the spread is 3%. This spread reflects the additional risk premium investors require for holding the corporate bond instead of the risk-free government bond. The spread can vary based on the creditworthiness of the issuer, economic conditions, and market sentiment. A wider spread typically indicates higher perceived risk or lower liquidity in the corporate bond. Investors monitor spreads closely to assess credit risk and make informed decisions in fixed income portfolios.

Table of Comparison

| Bond Type | Issuer Credit Rating | Yield (%) | Benchmark Yield (%) | Spread (bps) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Bond | BBB | 5.0 | 2.5 (10-Year Treasury) | 250 | Yield difference between corporate bond and US Treasury |

| High-Yield Bond | BB | 7.5 | 2.5 (10-Year Treasury) | 500 | Higher risk premium due to lower credit rating |

| Sovereign Bond | AAA | 1.5 | 1.0 (German Bund) | 50 | Risk premium over benchmark sovereign bond |

| Municipal Bond | AA | 3.0 | 1.8 (10-Year Treasury) | 120 | Spread reflecting tax-exempt status and credit risk |

Definition of Spread in Bond Markets

Spread in bond markets refers to the difference in yield between two bonds, often a corporate bond and a government bond of similar maturity, reflecting credit risk and liquidity. This yield spread measures the risk premium investors demand for bearing additional credit risk compared to a risk-free benchmark like U.S. Treasury bonds. Monitoring bond spreads helps investors gauge market sentiment, credit quality, and potential economic changes impacting fixed-income securities.

Key Types of Bond Spreads

Key types of bond spreads include the nominal spread, which measures the difference between a bond's yield and the risk-free rate, and the Z-spread, representing the constant yield spread added to the Treasury spot curve to price a bond. The option-adjusted spread (OAS) adjusts the Z-spread for embedded options such as call or put features, providing a clearer picture of credit risk. Swap spreads reflect the yield difference between a bond and interest rate swaps, indicating market perception of credit risk and liquidity.

Yield Spread Basics with Practical Examples

Yield spread in bonds measures the difference in yield between two bonds, typically comparing a corporate bond to a government bond of similar maturity to assess credit risk. For example, if a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yields 2% and a 10-year corporate bond yields 5%, the yield spread is 3%, indicating higher risk and potential return for the corporate bond. This spread reflects market perception of creditworthiness and liquidity, serving as a key indicator for investors evaluating bond investment opportunities.

Credit Spread Example in Corporate Bonds

Credit spread in corporate bonds represents the yield difference between a corporate bond and a comparable maturity government bond, reflecting the issuer's credit risk. For example, if a 5-year Treasury bond yields 2% and a 5-year corporate bond yields 5%, the credit spread is 3%, indicating higher compensation for default risk. This spread varies based on the company's credit rating, industry conditions, and overall economic environment, serving as a crucial indicator for investors assessing bond risk and return.

Government vs. Corporate Bond Spread Analysis

The government vs. corporate bond spread reflects the yield difference between corporate bonds and risk-free government securities, indicating credit risk and economic conditions. Typically, corporate bonds offer higher yields to compensate investors for increased default risk compared to government bonds, which are considered safer due to sovereign backing. Analyzing this spread helps investors assess credit risk premiums, market sentiment, and potential economic downturns.

Spread to Benchmark: Case Study

Spread to benchmark measures the difference in yield between a corporate bond and its corresponding government bond, indicating credit risk and liquidity. For example, if a 10-year corporate bond yields 5% while the 10-year Treasury bond yields 3%, the spread to benchmark is 200 basis points, reflecting the issuer's credit premium. Investors use this spread to assess relative value and risk when comparing bonds across different sectors and credit qualities.

Interpreting Option-Adjusted Spread (OAS)

Option-Adjusted Spread (OAS) measures the yield spread of a bond over the risk-free rate, adjusted for embedded options such as call or put features. It provides a more precise evaluation of credit and liquidity risks by isolating the impact of interest rate volatility and option costs on bond pricing. Investors use OAS to compare bonds with different option characteristics, ensuring a consistent basis for assessing relative value and potential returns.

Z-Spread Illustrated with Bond Examples

The Z-Spread, or zero-volatility spread, measures the constant yield spread over the entire Treasury yield curve that equates a bond's discounted cash flows to its market price. For example, a corporate bond with a Z-Spread of 150 basis points indicates it offers 1.5% more yield than the risk-free Treasury curve, compensating for credit and liquidity risks. Investors use the Z-Spread to evaluate relative value by comparing it across bonds with similar maturities but differing credit qualities.

Yield Curve Spread: Case Examples

Yield curve spread represents the difference in yield between bonds of varying maturities, providing insight into market expectations and interest rate risk. A common example is the spread between 2-year and 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds, which investors analyze to gauge economic outlook and potential recession signals. During periods of economic uncertainty, the yield curve spread often narrows or inverts, indicating investor concerns about future growth and influencing bond pricing strategies.

Real-World Factors Affecting Bond Spreads

Bond spreads, the difference in yield between corporate bonds and government securities, are heavily influenced by real-world factors such as credit risk, economic conditions, and market liquidity. For instance, during economic downturns, increased default risk widens spreads as investors demand higher compensation for riskier corporate debt. Changes in monetary policy and investor sentiment also directly impact bond spreads by altering the demand and perceived safety of bonds.

example of spread in bond Infographic

samplerz.com

samplerz.com