Stagflation in macroeconomy is characterized by the simultaneous occurrence of stagnant economic growth, high unemployment, and rising inflation. A notable example is the 1970s United States economy when oil price shocks led to soaring energy costs, causing inflation to rise while economic output growth slowed significantly. During this period, the Federal Reserve struggled to balance monetary policies as traditional tools to combat inflation risked worsening unemployment. The combination of slow GDP growth, rising consumer prices, and elevated unemployment rates showcases classic stagflation symptoms. Businesses faced higher production costs, reducing investments and hiring, creating a vicious cycle that impeded recovery efforts. Understanding stagflation is crucial for policymakers to develop strategies that address inflation without suppressing economic activity.

Table of Comparison

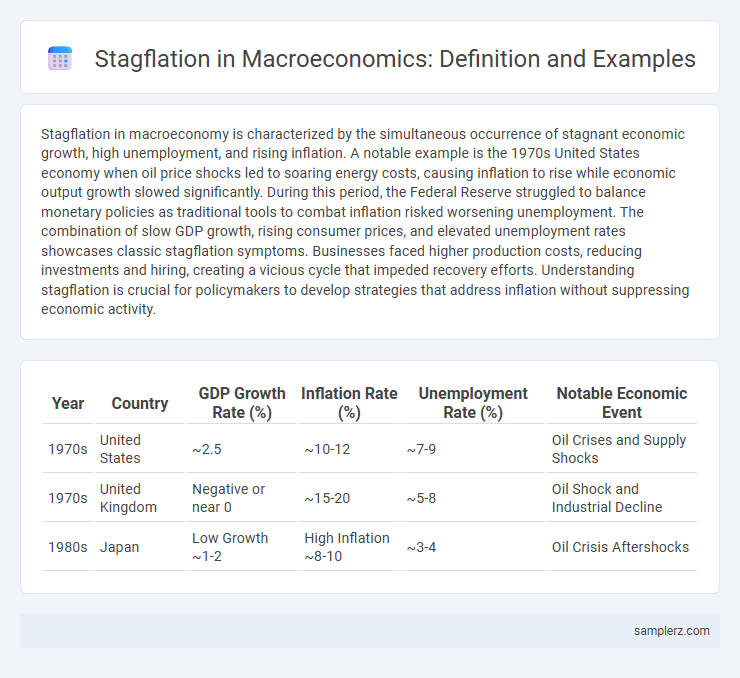

| Year | Country | GDP Growth Rate (%) | Inflation Rate (%) | Unemployment Rate (%) | Notable Economic Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s | United States | ~2.5 | ~10-12 | ~7-9 | Oil Crises and Supply Shocks |

| 1970s | United Kingdom | Negative or near 0 | ~15-20 | ~5-8 | Oil Shock and Industrial Decline |

| 1980s | Japan | Low Growth ~1-2 | High Inflation ~8-10 | ~3-4 | Oil Crisis Aftershocks |

Defining Stagflation: Key Economic Indicators

Stagflation is characterized by the unusual combination of high inflation rates, stagnant economic growth, and elevated unemployment levels, complicating traditional economic policy responses. Key economic indicators include a rising Consumer Price Index (CPI) alongside flat or negative Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth and increasing jobless claims. This phenomenon challenges monetary and fiscal policies as measures to curb inflation often exacerbate unemployment, while efforts to boost growth may intensify inflationary pressures.

Historical Overview: The 1970s Stagflation Crisis

The 1970s stagflation crisis was characterized by stagnant economic growth, high unemployment, and soaring inflation, a rare macroeconomic phenomenon defying traditional economic theory. The period saw oil price shocks from OPEC leading to supply-side constraints, which significantly contributed to rising consumer prices and declining industrial production. Central banks struggled to balance monetary policies, as measures to curb inflation risked worsening unemployment and vice versa.

Global Examples of Stagflation Scenarios

The 1970s oil crisis triggered a global stagflation scenario marked by simultaneous high inflation, rising unemployment, and stagnant economic growth across developed economies such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions combined with expansive fiscal policies led to stagflation-like conditions in emerging markets including Turkey and Argentina. These examples highlight the complex interplay between supply shocks and monetary factors that drive stagflation in diverse macroeconomic environments.

Causes of Stagflation in Macroeconomics

Stagflation in macroeconomics typically arises from a combination of supply shocks, such as sudden increases in oil prices, and inappropriate monetary policies that fail to control inflation without stifling growth. Structural rigidities in the labor market and decreased productivity also contribute to the persistent coexistence of high inflation and unemployment. These causes disrupt the normal trade-off between inflation and unemployment described by the Phillips curve, leading to prolonged economic stagnation alongside rising prices.

The Oil Shock and Its Impact on Inflation and Unemployment

The Oil Shock of the 1970s exemplifies stagflation as soaring oil prices caused inflation to surge while economic growth stagnated and unemployment rose. This supply-side shock disrupted production costs globally, leading to higher consumer prices without corresponding wage increases. The resulting economic environment challenged traditional macroeconomic policies, highlighting the complexity of controlling inflation and unemployment simultaneously.

Stagflation in Emerging Markets: Case Studies

Stagflation in emerging markets, such as Brazil during the 1980s debt crisis, exemplifies the challenges of simultaneous high inflation and stagnant growth amid external shocks and fiscal imbalances. Another critical case is Turkey in the late 1990s and early 2000s, where inflation rates soared above 50% while GDP growth remained sluggish due to currency volatility and political instability. These instances demonstrate that emerging economies are particularly vulnerable to stagflation driven by structural weaknesses, commodity price fluctuations, and inconsistent monetary policies.

Policy Responses to Stagflation: Successes and Failures

During the 1970s stagflation, U.S. policymakers faced rising inflation and stagnant growth, implementing tight monetary policies that curbed inflation but deepened unemployment. Fiscal policies aimed at stimulating demand often worsened inflationary pressures without boosting output, highlighting a trade-off between inflation control and growth. The mixed outcomes underscored the challenges in balancing anti-inflation measures with employment, influencing contemporary macroeconomic strategies.

Lessons Learned from Past Stagflation Events

Historical stagflation events, such as the 1970s oil crisis, demonstrated the dangers of simultaneous high inflation and stagnant economic growth driven by supply shocks and poor monetary policy. Central banks learned the necessity of maintaining credible inflation targets and the risks of accommodative policies that ignore supply constraints. These lessons emphasize the importance of coordinated fiscal and monetary responses to avoid prolonged economic stagnation coupled with inflation.

Stagflation Risks in the Modern Global Economy

Stagflation risks in the modern global economy are highlighted by persistent inflation rates above 5% alongside stagnant GDP growth below 1%, as observed in several advanced economies since 2022. Supply chain disruptions, labor market rigidities, and aggressive monetary tightening by central banks contribute to rising unemployment and declining consumer demand. Emerging markets face heightened vulnerabilities due to increased commodity prices and currency depreciation, exacerbating inflationary pressures amidst weak economic expansion.

Preventing and Managing Stagflation in the Future

Preventing and managing stagflation requires coordinated monetary and fiscal policies that target both inflation control and unemployment reduction simultaneously. Central banks must carefully balance interest rate adjustments to avoid triggering economic stagnation while implementing supply-side reforms that enhance productivity and reduce production costs. Investing in technological innovation and diversifying energy sources can mitigate future supply shocks, thereby stabilizing prices and supporting sustainable economic growth.

example of stagflation in macroeconomy Infographic

samplerz.com

samplerz.com