Ricardian equivalence is an economic theory suggesting that government debt does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future taxes to repay the debt. For example, if a government finances a stimulus package through borrowing, rational consumers may increase their savings to pay for the expected future tax increase. This behavior neutralizes the intended boost to aggregate demand since private savings offset government spending. Empirical evidence of Ricardian equivalence can be seen in countries with high government debt, where consumers demonstrate conservative spending patterns. Data from economies such as Japan and Germany indicate that despite increased public borrowing, household saving rates tend to rise in anticipation of tax liabilities. This phenomenon challenges traditional fiscal policy assumptions by showing limited impact of debt-financed expenditure on macroeconomic activity.

Table of Comparison

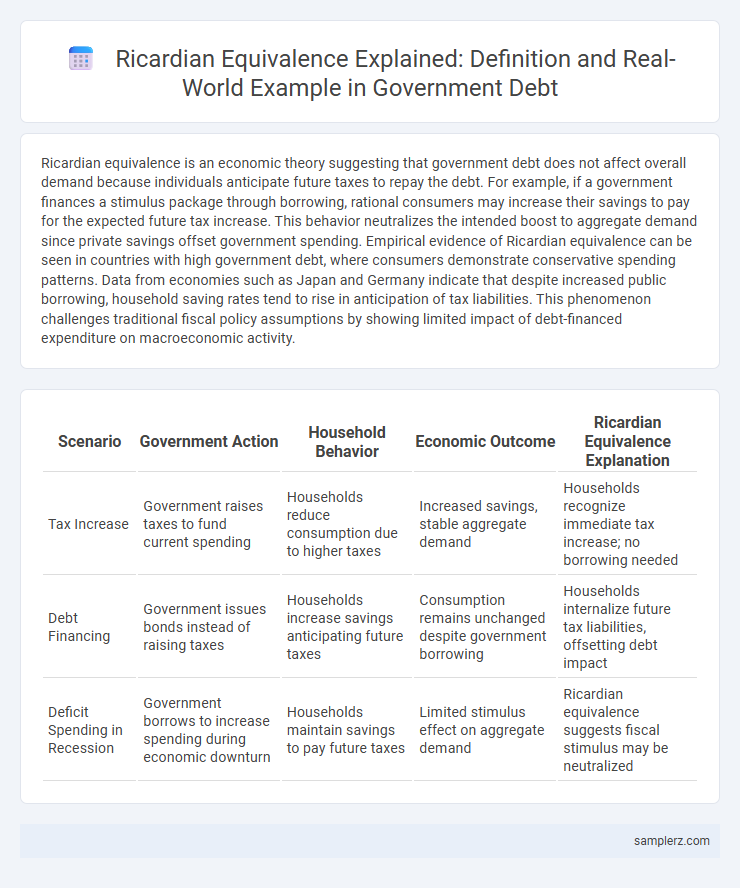

| Scenario | Government Action | Household Behavior | Economic Outcome | Ricardian Equivalence Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax Increase | Government raises taxes to fund current spending | Households reduce consumption due to higher taxes | Increased savings, stable aggregate demand | Households recognize immediate tax increase; no borrowing needed |

| Debt Financing | Government issues bonds instead of raising taxes | Households increase savings anticipating future taxes | Consumption remains unchanged despite government borrowing | Households internalize future tax liabilities, offsetting debt impact |

| Deficit Spending in Recession | Government borrows to increase spending during economic downturn | Households maintain savings to pay future taxes | Limited stimulus effect on aggregate demand | Ricardian equivalence suggests fiscal stimulus may be neutralized |

Real-World Illustrations of Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian equivalence is exemplified in real-world cases such as the U.S. during the 1980s where increased government borrowing to fund tax cuts led many households to save more, anticipating future tax hikes. Empirical studies in countries like Japan have also shown mixed evidence, with some consumers offsetting government debt through increased savings while others do not. These illustrations highlight the varying degrees to which Ricardian equivalence holds depending on consumer expectations and fiscal policy transparency.

Government Debt and Household Savings: Practical Cases

Government debt issuance often leads households to increase their savings, anticipating future tax hikes to repay the debt, exemplifying Ricardian equivalence. For instance, during periods of large fiscal deficits in the United States, empirical studies have shown that households adjust their savings rates upward to offset government borrowing. This behavioral response highlights the interplay between government debt and household savings, influencing national saving rates and fiscal policy effectiveness.

Empirical Examples of Ricardian Equivalence in Action

Empirical examples of Ricardian equivalence in government debt include studies on the United States during the 1980s tax cuts, where consumers increased savings anticipating future tax hikes, aligning with Ricardian predictions. Research on Japan's prolonged fiscal stimulus in the 1990s also exhibited limited impact on consumption, supporting the notion that households internalize government budget constraints. These cases demonstrate how forward-looking behavior influences the effectiveness of fiscal policy through intertemporal substitution and wealth effects.

How Tax Anticipation Shapes Consumer Behavior

Ricardian equivalence suggests that when governments increase debt to finance spending, consumers anticipate future tax hikes and adjust their savings accordingly. This behavior diminishes the stimulative effect of deficit spending because consumers save more to pay for expected taxes instead of increasing consumption. Empirical studies show that households with higher financial literacy exhibit stronger tax anticipation, reinforcing the idea that consumer expectations play a crucial role in shaping economic outcomes under government debt policies.

Case Studies: Fiscal Policy and Ricardian Responses

Government debt increases funded by deficit spending often lead households to anticipate future tax hikes, prompting them to save rather than spend, as demonstrated in U.S. post-2008 fiscal stimulus measures. Empirical studies in OECD countries reveal that despite significant stimulus efforts, private savings rates rose, aligning with Ricardian equivalence predictions where consumers internalize government budget constraints. These case studies underscore the complex interaction between fiscal policy and household consumption, challenging the efficacy of deficit spending in stimulating aggregate demand.

Evidence of Ricardian Equivalence in Modern Economies

Empirical studies on Ricardian equivalence in modern economies show mixed evidence, with some research indicating that increased government debt leads to higher private savings as households anticipate future tax burdens. For instance, data from OECD countries during periods of fiscal expansion reveal partial substitution between public debt and private savings, supporting the Ricardian hypothesis to an extent. However, factors such as liquidity constraints and myopic behavior often limit the full manifestation of Ricardian equivalence in practice.

Government Borrowing: Private Sector Offsets Explained

Government borrowing does not necessarily increase overall demand when the private sector anticipates future tax hikes to repay debt, leading to increased private savings. This behavior, known as Ricardian equivalence, demonstrates that individuals offset government deficits by reducing consumption, maintaining their intertemporal budget constraints. Empirical evidence suggests that in economies with rational agents and perfect capital markets, government debt issuance may have limited effects on aggregate demand due to these private sector responses.

Testing Ricardian Equivalence: Notable Historical Episodes

Historical episodes testing Ricardian equivalence include the 1980s U.S. tax-cut experiments and Japan's prolonged fiscal stimulus in the 1990s, where increased government debt did not lead to proportional changes in private saving behavior. Empirical studies during these periods analyzed household consumption patterns, revealing mixed evidence on whether consumers fully anticipated future tax burdens implied by government borrowing. The findings suggest that Ricardian equivalence holds under specific conditions, such as perfect capital markets and rational expectations, but often deviates in real-world fiscal environments.

Policy Outcomes: When Ricardian Equivalence Holds True

When Ricardian Equivalence holds true, government debt issuance does not affect overall demand because consumers anticipate future tax increases to repay the debt and adjust their savings accordingly. This behavior neutralizes the stimulative impact of fiscal deficits on aggregate consumption and economic growth. Empirical evidence suggests that in economies with forward-looking households and perfect capital markets, deficit financing fails to boost short-term output or reduce interest rates.

Lessons from Ricardian Equivalence: Insights for Policymakers

Ricardian Equivalence suggests that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future taxes to repay debt and thus increase their savings accordingly. Policymakers must recognize that deficit financing might not stimulate economic growth if households adjust their behavior to offset government debt issuance. Effective fiscal strategies should consider Ricardian Equivalence to design policies that influence real consumption and investment rather than rely solely on borrowing.

example of Ricardian equivalence in government debt Infographic

samplerz.com

samplerz.com