A line-item veto is a budgetary power allowing a government executive to reject specific provisions or expenditures in a spending bill without vetoing the entire legislation. This tool is commonly used by governors and the President in some jurisdictions to control excessive or unnecessary spending by removing particular budget items. For example, a governor might exercise a line-item veto to eliminate funding for a controversial highway project while approving the remaining state budget. In the federal government context, the U.S. President once had limited line-item veto authority under the Line Item Veto Act of 1996, which allowed vetoing specific spending items in appropriations bills. The Supreme Court struck down this act as unconstitutional in 1998 because it gave the executive branch the power to unilaterally amend laws passed by Congress. State governments continue to use the line-item veto as a key mechanism for fiscal oversight and budgetary precision.

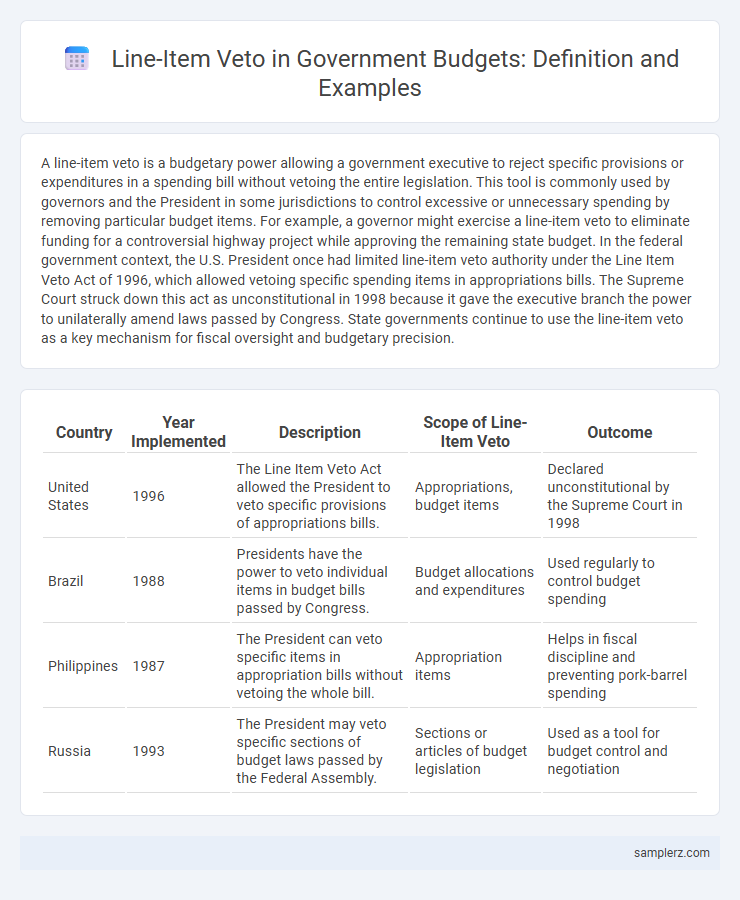

Table of Comparison

| Country | Year Implemented | Description | Scope of Line-Item Veto | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 1996 | The Line Item Veto Act allowed the President to veto specific provisions of appropriations bills. | Appropriations, budget items | Declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1998 |

| Brazil | 1988 | Presidents have the power to veto individual items in budget bills passed by Congress. | Budget allocations and expenditures | Used regularly to control budget spending |

| Philippines | 1987 | The President can veto specific items in appropriation bills without vetoing the whole bill. | Appropriation items | Helps in fiscal discipline and preventing pork-barrel spending |

| Russia | 1993 | The President may veto specific sections of budget laws passed by the Federal Assembly. | Sections or articles of budget legislation | Used as a tool for budget control and negotiation |

Understanding the Line-Item Veto Power

The line-item veto power allows governors or executives to reject specific provisions or expenditures in a budget bill without vetoing the entire legislative package, enhancing fiscal control and preventing unnecessary spending. For example, the governor of Texas can delete particular budget items that are deemed wasteful while approving the remaining appropriations, streamlining government spending. Courts have often ruled on the constitutional limits of line-item veto, shaping its implementation within various states and influencing federal discussions on budgetary authority.

Historical Overview of Line-Item Veto in Budgeting

The line-item veto, first introduced in the United States in the early 20th century, allowed presidents to selectively veto specific provisions of budget bills without rejecting the entire package. Notably, President Grover Cleveland used this power in the 1880s at the state level, setting a precedent that influenced later federal adoption. The Line Item Veto Act of 1996 marked a significant federal attempt to expand this authority, though it was ultimately ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1998, shaping ongoing debates about executive power in budgeting.

Landmark Cases of Line-Item Veto Usage

The landmark case Raines v. Byrd (1997) challenged the constitutionality of the Line Item Veto Act, where Congress aimed to enhance budget control by allowing the President to cancel specific spending items. Another significant case, Clinton v. City of New York (1998), resulted in the Supreme Court ruling the Line Item Veto Act unconstitutional, emphasizing the violation of the Presentment Clause. These cases set critical precedents governing the legality and limits of line-item veto powers within federal budget processes.

Federal vs State Application of Line-Item Veto

The line-item veto allows executives to reject specific budget provisions without vetoing the entire legislative bill, used differently at federal and state levels. At the federal level, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the presidential line-item veto unconstitutional in Clinton v. City of New York (1998), limiting its application. Conversely, many state governors possess broad line-item veto powers to selectively eliminate budget items, enhancing fiscal control and limiting spending within state budgets.

Notable Presidential Line-Item Veto Examples

President Ronald Reagan exercised the line-item veto in 1987, canceling $98 million in wasteful spending from a $1.2 trillion budget, marking a significant use of this power. Bill Clinton used the line-item veto over 80 times in 1996 to eliminate pork-barrel projects, demonstrating its role in fiscal restraint. These actions highlight the line-item veto's impact on controlling federal expenditures before the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1998.

Significant State Governors’ Line-Item Veto Actions

Significant state governors' line-item veto actions have notably influenced budgetary outcomes by selectively removing specific expenditures to control state deficits and redirect funds toward priority programs. For example, Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York exercised the line-item veto to cut millions in spending on projects deemed non-essential, enhancing fiscal discipline during budget negotiations. Similarly, Texas Governor Greg Abbott has used this power to eliminate unnecessary appropriations, reinforcing targeted investments in public safety and education while maintaining balanced budgets.

Political Implications of Line-Item Veto Decisions

The political implications of line-item veto decisions often influence budget allocations by allowing executives to remove specific expenditures, thereby shaping policy priorities and power dynamics within government. This selective cancellation can provoke legislative pushback or negotiation, as lawmakers may perceive the veto as an encroachment on budgetary authority. The strategic use of line-item vetoes thus impacts party relations, agenda-setting, and overall governance efficacy.

Legal Challenges to the Line-Item Veto

The line-item veto, a budgetary power allowing executives to reject specific provisions without vetoing an entire bill, has faced significant legal challenges, notably in the U.S. Supreme Court case Clinton v. City of New York (1998). The Court ruled the Line Item Veto Act unconstitutional, asserting it violated the Presentment Clause by allowing the president to unilaterally amend legislation passed by Congress. This decision underscored the constitutional limits of executive authority in budgetary processes and shaped subsequent government approaches to fiscal control.

Impact of Line-Item Vetoes on Government Spending

The implementation of line-item vetoes enables governors and the president to selectively reject specific budget items, directly reducing unnecessary or excessive government expenditures. This power promotes fiscal discipline by allowing targeted cuts without vetoing entire legislative bills, leading to more efficient allocation of taxpayer funds. Studies show that jurisdictions with active line-item veto authority often experience slower growth in government spending and improved budgetary control.

Future Prospects for Line-Item Veto Authority

Future prospects for line-item veto authority include increased adoption by state governments seeking greater fiscal control and reduced budgetary waste. Emerging technologies in data analytics enhance the ability to identify unnecessary expenditures, potentially expanding the effectiveness of line-item vetoes. Legislative debates continue to weigh constitutional challenges against the potential for improved budget precision and transparency.

example of line-item veto in budget Infographic

samplerz.com

samplerz.com