A notable example of no-confidence in parliament occurred in the United Kingdom in 1979. The Labour government, led by Prime Minister James Callaghan, faced a vote of no-confidence due to economic challenges and internal party divisions. The motion passed by a single vote, leading to the dissolution of Parliament and triggering a general election. Another significant case took place in India in 1999 when the coalition government led by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee lost a no-confidence motion. The government failed to secure a majority after withdrawing support from a key ally. This event highlighted the fragile nature of coalition politics in parliamentary systems with multiple political parties.

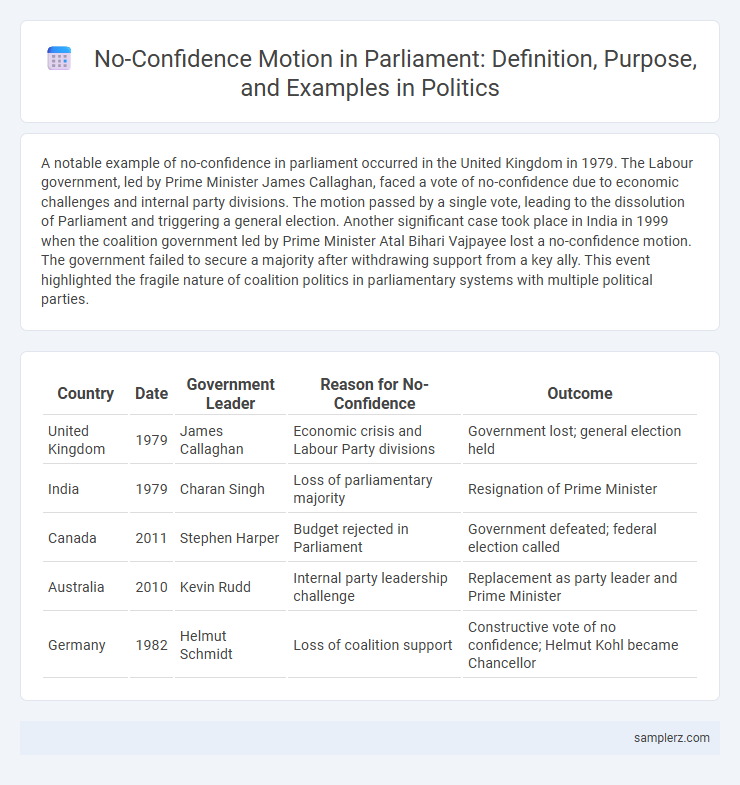

Table of Comparison

| Country | Date | Government Leader | Reason for No-Confidence | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 1979 | James Callaghan | Economic crisis and Labour Party divisions | Government lost; general election held |

| India | 1979 | Charan Singh | Loss of parliamentary majority | Resignation of Prime Minister |

| Canada | 2011 | Stephen Harper | Budget rejected in Parliament | Government defeated; federal election called |

| Australia | 2010 | Kevin Rudd | Internal party leadership challenge | Replacement as party leader and Prime Minister |

| Germany | 1982 | Helmut Schmidt | Loss of coalition support | Constructive vote of no confidence; Helmut Kohl became Chancellor |

Overview of No-Confidence Motions in Parliamentary Systems

No-confidence motions serve as a critical mechanism in parliamentary systems, allowing legislatures to withdraw support from the ruling government, often leading to its resignation or the dissolution of parliament. These motions are typically initiated by opposition parties and require a majority vote to pass, reflecting a loss of political legitimacy or government effectiveness. Prominent examples include the 1979 no-confidence vote against the UK Labour government and the 2019 defeat of the Indian government's budget proposal, both illustrating how such motions uphold democratic accountability.

Historical Examples of No-Confidence Votes

In 1979, the United Kingdom witnessed a pivotal no-confidence vote when Prime Minister James Callaghan's Labour government lost by a single vote, triggering a general election that led to Margaret Thatcher's rise. India's 1963 no-confidence motion against Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru marked a significant moment in parliamentary democracy, showcasing the robustness of legislative scrutiny. In Australia, the 1975 constitutional crisis culminated in a no-confidence vote that resulted in the dismissal of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, highlighting the power dynamics between the executive and the parliament.

Notable No-Confidence Cases in Modern Politics

Notable no-confidence cases in modern politics include the 1979 no-confidence vote against UK Prime Minister James Callaghan, which led to Margaret Thatcher's rise. In 2019, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi survived a no-confidence motion amidst significant opposition challenges. The 2010 no-confidence vote in Pakistan saw then-Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gillani retain power despite allegations of corruption, highlighting the political volatility in parliamentary democracies.

Key Factors Leading to Parliamentary No-Confidence

Key factors leading to parliamentary no-confidence include widespread public dissatisfaction with government policies, failure to address economic crises such as inflation or unemployment, and internal party divisions weakening leadership cohesion. Corruption scandals and loss of support from coalition partners frequently precipitate votes of no-confidence. Electoral pressure and shifts in public opinion polls often signal impending challenges to the sitting government's stability.

The Process of Initiating a No-Confidence Vote

The process of initiating a no-confidence vote in parliament begins with a formal proposal submitted by a specified minimum number of members, often outlined in parliamentary rules. This motion requires precise wording and is typically debated before a scheduled vote takes place within a designated timeframe. If the motion passes by a majority, it compels the resignation of the government or cabinet, triggering political reorganization or new elections.

Major Outcomes of Successful No-Confidence Motions

Successful no-confidence motions in parliament often lead to the resignation of the sitting government, triggering either the formation of a new coalition or fresh general elections. These outcomes shift the balance of power, impacting legislative agendas and policy directions significantly. Notable cases include the 1979 UK no-confidence vote that ended James Callaghan's government, leading to Margaret Thatcher's premiership.

Impact on Government and Political Stability

A no-confidence vote in parliament often leads to the resignation or dismissal of the current government, triggering a reshuffle or new elections that can alter the political landscape. This mechanism ensures accountability but frequently causes short-term instability, affecting policy continuity and investor confidence. Repeated no-confidence motions can weaken governance structures and exacerbate factionalism within political parties.

Differences Between No-Confidence and Censure Motions

No-confidence motions directly challenge the entire government's legitimacy, requiring the executive to resign if passed, while censure motions address specific individual ministers or policies without necessarily dissolving the government. No-confidence motions often trigger elections or government reshuffles, whereas censure motions function as formal disapprovals that may or may not lead to consequences such as resignation or policy changes. The procedural thresholds and political implications of both motions vary significantly across parliamentary systems, reflecting different balances of power and political stability mechanisms.

International Comparisons of No-Confidence Examples

The 2019 no-confidence vote in the UK Parliament, initiated against Prime Minister Theresa May, exemplifies the parliamentary mechanism to challenge executive leadership. In contrast, India's 1999 no-confidence motion against Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee emphasized coalition dynamics and political stability in a multiparty system. Germany's Bundestag rarely sees no-confidence votes, but the 1982 constructive vote of no confidence successfully replaced Chancellor Helmut Schmidt with Helmut Kohl, highlighting a unique approach requiring a prospective successor.

Lessons Learned from Parliamentary No-Confidence Precedents

Parliamentary no-confidence motions, such as the 1979 UK defeat of James Callaghan's government, demonstrate the vital importance of maintaining coalition unity and effective communication among party members to avoid sudden political collapses. The 2018 Indian no-confidence motion against Prime Minister Narendra Modi revealed that strong parliamentary majorities and strategic alliance-building can effectively counter opposition challenges and preserve governmental stability. These precedents highlight how no-confidence votes serve as critical barometers of legislative support, emphasizing the necessity for continuous political negotiation and adaptive leadership within parliamentary democracies.

example of no-confidence in parliament Infographic

samplerz.com

samplerz.com